Garden & Gun: Drinks – The New Rumrunners

Small-batch distilleries are helping rum reclaim its rightful place in the well-stocked Southern bar.

Umbrella drinks, pirates, and Malibu—few spirits have as checkered a reputation as rum. These days, it’s known mostly as party fuel. “Many people come to rum with memories that unfortunately involve a bottle of Bacardi and their neighbor’s shrubbery,” says Wayne Curtis, the author of And a Bottle of Rum: A History of the New World in Ten Cocktails. But a growing number of Southern distillers are taking rum back to its more respectable roots, producing blends to be savored, not slugged.

Bourbon may have a hold on the South’s self-image, but rum goes back even further: The cultivation of sugarcane, its base ingredient, dates back to the region’s colonial days. “You make what you grow,” says Kelly Railean, the owner of Railean Distillers in San Leon, Texas, along the Gulf Coast. She opened in 2007, becoming one of the South’s first new-school rum distillers. Scores of distilleries operated along the Gulf Coast before both the Civil War and the onset of state-level Prohibition in the late nineteenth century wiped them out. Americans later fell in love with the sweetened mass-produced rums coming out of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, drinks that are hard to take straight but mix well in the neon-colored concoctions that, over the years, have come to typify rum’s presence at the bar.

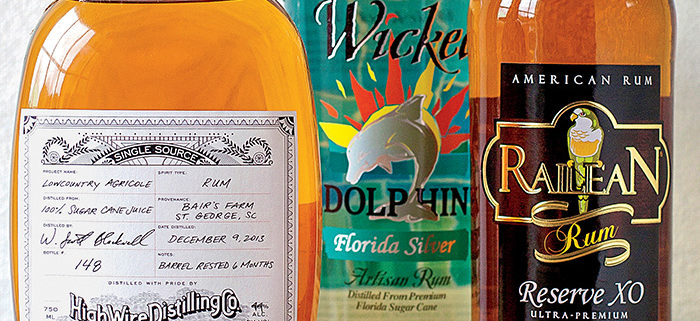

Now, though, distillers are learning to appreciate rum’s complexity and variety. Both Prichard’s in Tennessee and Old New Orleans Rum in Louisiana offer limited-edition aged rums almost old enough to drive a car, with the smooth vanilla and caramel notes of a fine bourbon. Scott and Ann Blackwell, who opened Charleston, South Carolina’s High Wire Distilling in 2013, started with a molasses-based rum but now produce rhum agricole, a style made with freshly squeezed cane juice and most commonly associated with the French island of Martinique. High Wire’s cane comes from small patches near Charleston, with the name of the originating farm on each bottle. The result is a delicate, sweetly grassy spirit—the last thing you’d dump into an eighties-era mai tai.

Bartenders are rediscovering rum’s versatility, too. “Because it’s so loosely regulated, rum is the Wild West when it comes to variety,” says Duane Sylvester of Bourbon Steak in Washington, D.C. “It’s amazing to see what people are able to do.” One popular trick is to swap rum for whiskey in an old-fashioned or a Boulevardier, or to sub in rhum agricole for tequila in a Paloma. “These days we sell more rum than vodka drinks,” says Andy Minchow, the owner of Ration and Dram, a cocktail bar in Atlanta’s Edgewood neighborhood.

Around New Orleans’ Decatur Street, so many rum-centric bars—Latitude 29, Cane and Table, Tiki Tolteca—have emerged in the last two years that folks have started calling it Rum Row. WunderBar, which recently opened in Miami’s Circa 39 hotel, has more than sixty-five different bottles on its shelves. And while many of these bars have lengthy cocktail menus, bartenders aren’t afraid to offer extra-aged rums to sip straight, too. “Rums can drink like Armagnacs, like cognacs, like bourbon,” says Cane and Table’s co-owner Nick Detrich.

But all of the high-mindedness doesn’t mean rum can’t remain the life of the party. Take tiki drinks, which are making yet another comeback. “The last few years have been very serious,” says Russell Theode, co-owner of the tiki-themed Lei Low bar in Houston, “but tiki is fun.” Eschewing tropical kitsch for forgotten recipes, fewer ingredients, and fresh fruit juices, Theode and his rum-loving brethren aim to highlight and complement the spirit’s flavor, rather than mask it—which, given the diversity and quality of rum styles available, makes for a wealth of options. “If someone says they don’t like rum,” he says, “they just haven’t found the right one yet.”